As was true across the country, African Americans in Erie were hit especially hard by the Great Depression. Unemployment rates were twice that of white citizens, surpassing 50 percent in Pittsburgh and Erie in the worst years of the decade. The situation in the South was even more grave, with cities like Atlanta reporting nearly three of four blacks without work. Such grim conditions prompted a spike in the exodus of African Americans from the South to northern cities like Erie.

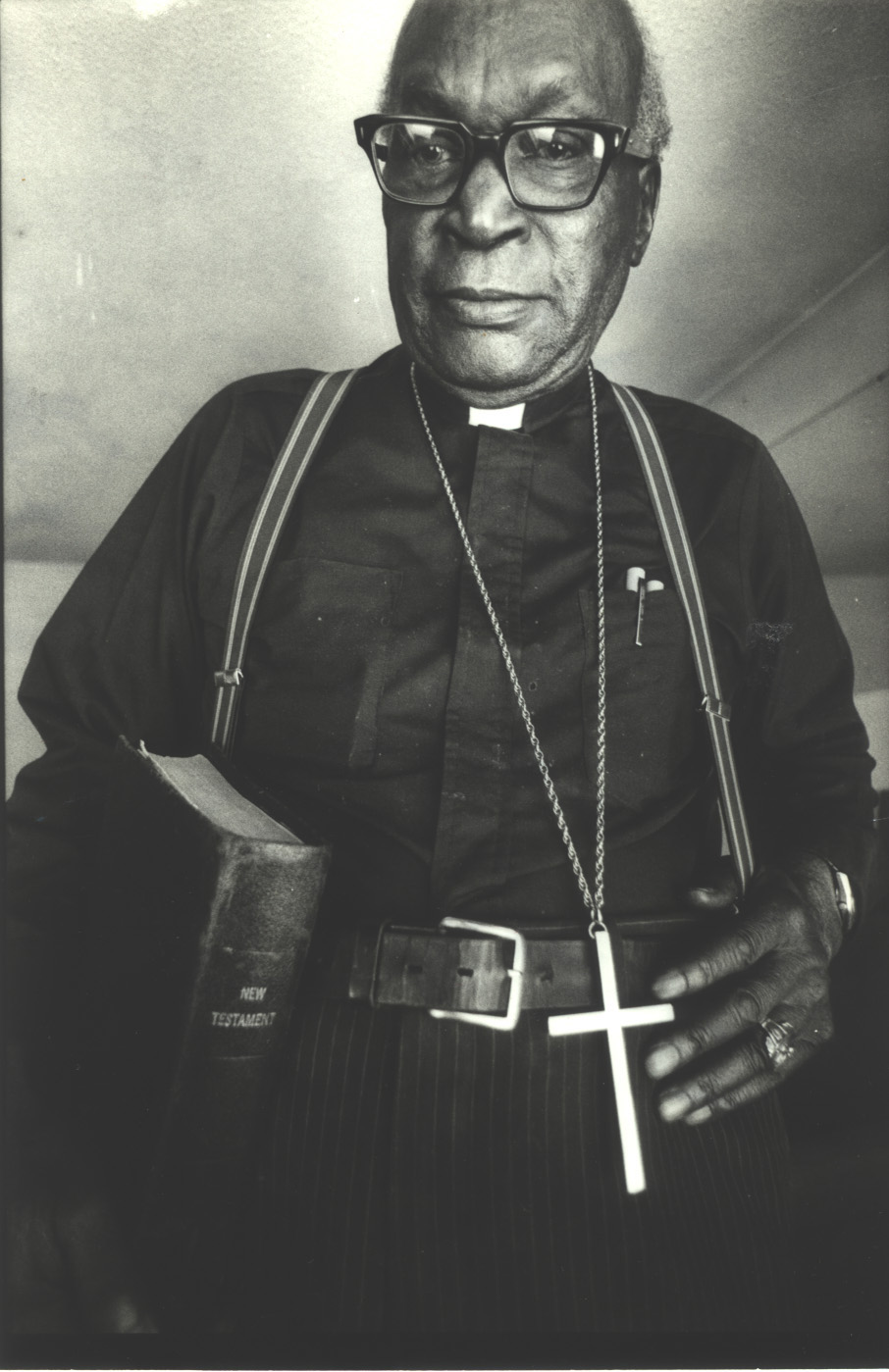

They were encouraged to do so by figures like Reverend Ernest Franklin Smith, who in 1934 established the Good Samaritan AME Zion Church in the 1100 block of Walnut Street. From his church and Negro Welfare Mission next door, Smith began actively recruiting black Americans, many of them from Laurel, Mississippi, to come to Erie. By the late-twentieth century when the African American population reached ten percent of the city, nearly one-half of them could claim family roots in Laurel. Many Laurel natives were alumni of Oak Park High School, which Fred Rush later said provided “seed corn” for a growing sense of pride and accomplishment in the African American community. Reverend Smith’s recruitment work did not come without risk, as powerful Southern interests feared, resisted (sometimes violently in the shadows), and testified in congress against the migration of blacks to northern cities, notably including Erie.

Once migrants arrived in Erie, Smith worked to find them employment and housing. In addition, the Negro Welfare Mission operated a nursery school, fed hungry children, taught adult education classes, and worked to improve sanitary conditions across the city. Rev. E.F. Smith’s extraordinary legacy continues today in the work of the E.F. Smith Quality of Life Learning Center (see oral history interview with Gary Horton under “Historical Voices”.)

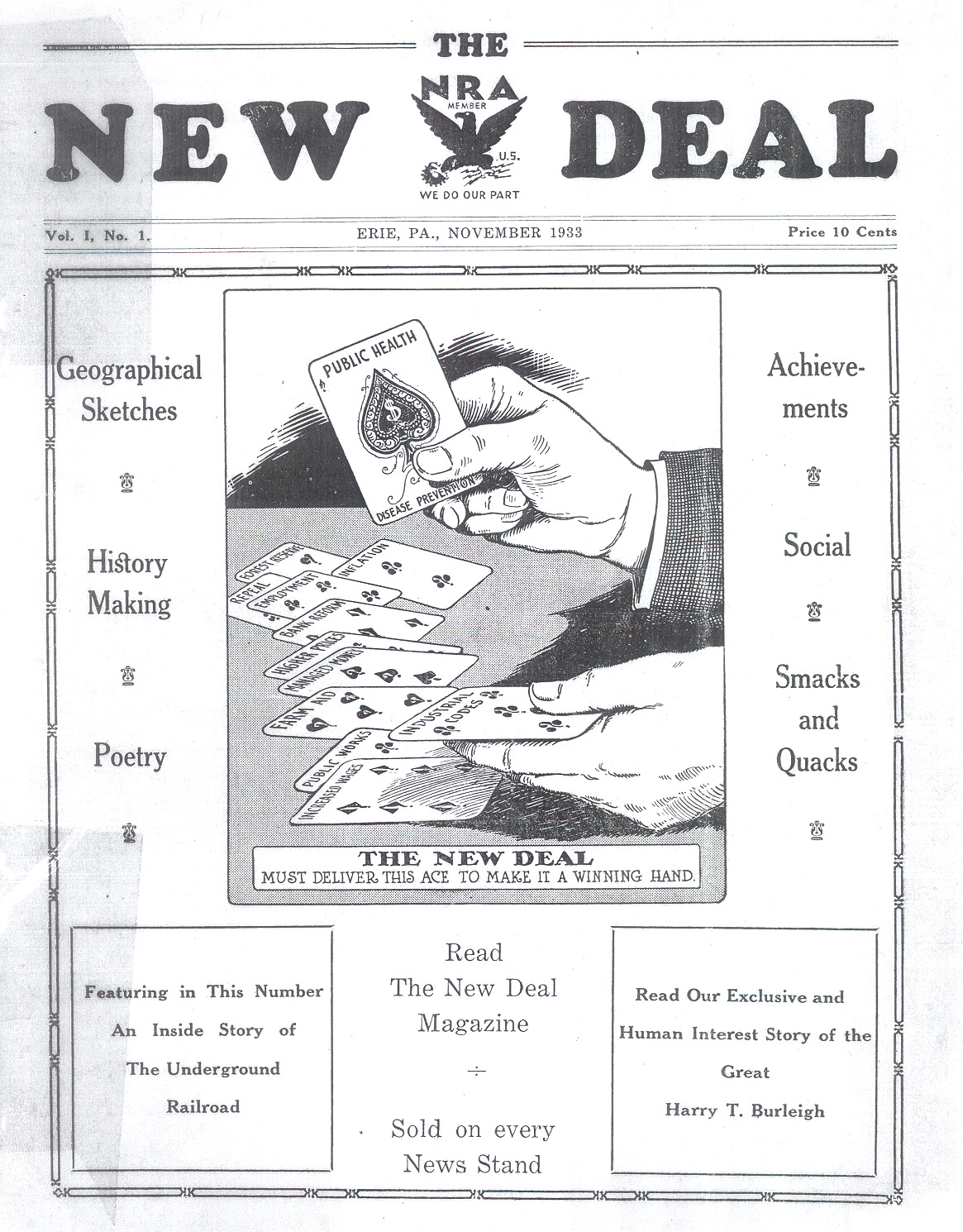

The economic crisis brought calls for social and economic justice reverberating around the country, including Erie. In 1933, the worst year of the Great Depression, Earl E. Lawrence published the inaugural edition of a magazine called The New Deal. The publication’s namesake was an homage to the program of sweeping social and economic reform being advanced by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.The New Deal’s mission was promoting “wherever possible the interests of the negro,” but more broadly—in keeping with the New Deal coming out of Washington—“the advancement of anything it considers to be for the great and general good of all the people.” The magazine pledged to “fight for improved housing facilities…and general health conditions… [and] against crookedness in high public places, fall where the chips may.”

Throughout its several years of publication, The New Deal discussed matters that remain hauntingly relevant nearly a century later, including the harmful effects of flying the Confederate flag, the power of “the colored vote” and the urgent need for the poor to unite across color lines for the common good, and the scourge of police brutality against people of color.

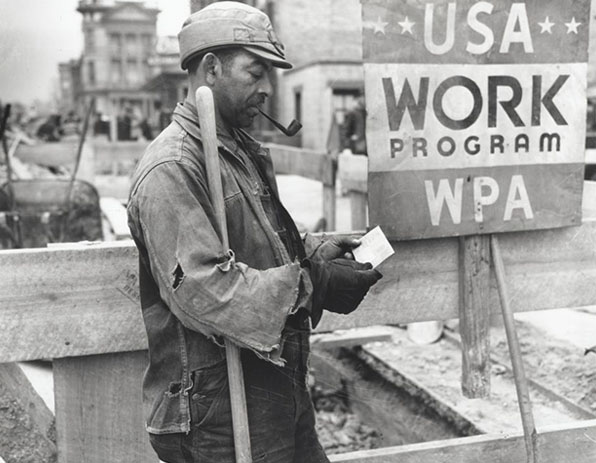

Although the New Deal of FDR failed African Americans in key respects—Roosevelt’s tragic refusal to support an anti-lynching bill, for example, because he needed the votes of conservative Southern congressman to advance legislation—blacks had good reason to abandon their allegiance to the “party of Lincoln” and support Democrat Franklin Roosevelt. A number of black men from Erie worked for “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” the Civilian Conservation Corps at CCC camps in Allegheny National Forest. Others labored on local Works Progress Administration projects like improvements at the Pennsylvania Soldiers and Sailors Home or Erie International Airport.

3. Earl Lawrence (upper left) with students from Erie and Crawford Counties enrolled in the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Music Program, which Mr. Lawrence helped lead.

4. Works Progress Administration Worker Receiving Paycheck; 1/1939

Many businesses did not survive the hard times of the 30s. One that did was William and Jessie Pope’s Hotel Pope (the “Pope Hotel” to most) at 1318 French Street, established just prior to the Wall Street crash. A leader in the NAACP, Jessie was the primary manager of the hotel until 1933 when her son Ernie Wright Sr. assumed oversight. It was Wright who began bringing to the Pope musical luminaries like Duke Ellington, Pearl Bailey, Jackie Wilson, and Lionel Hampton. Though black entertainers were prohibited from staying at nearby hotels by virtue of the defacto segregation that prevailed in many sectors of the city, the Pope Hotel welcomed black and white patrons to dine, sleep, or dance to some of America’s greatest musicians.

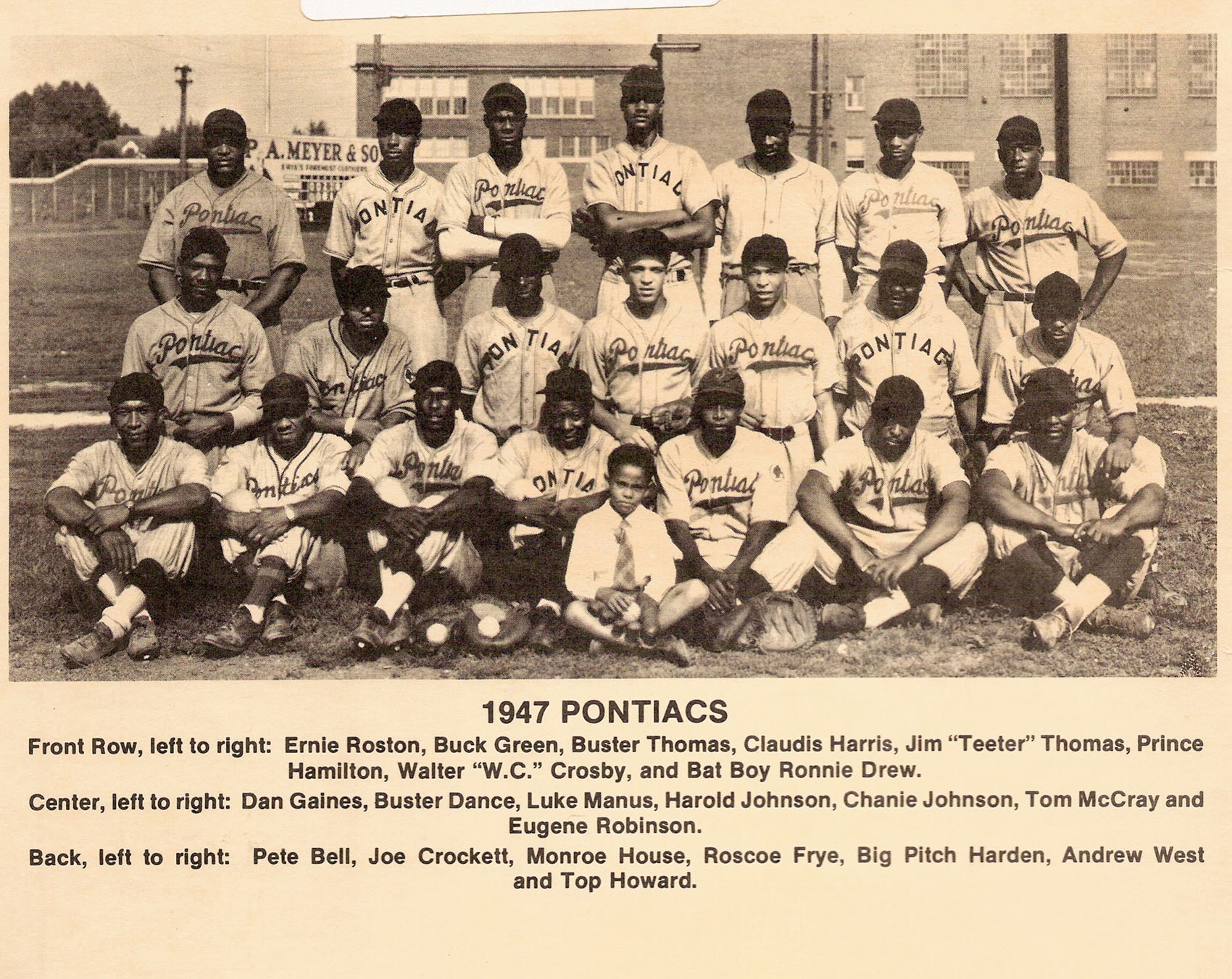

As was the case elsewhere in Depression America, the “national pastime” of baseball entertained many in Erie. Indeed, out of this difficult decade emerged the city’s most famous African American sports team, the semiprofessional Glenwood League Pontiacs. Growing out of a St. James A.M.E. Sunday School team, the Pontiacs drew large crowds at Jerusalem’s Bayview Park, particularly when they grafted onto their squad a number of players from the former Cleveland Buckeyes, that city’s formidable Negro League team. The Buckeyes, dominant winners of the 1945 Negro World Series, were owned by Ernie Wright of the Pope Hotel, who opened the pipeline for former Buckeyes, including future Major Leaguers Willie Grace and Sam Jethroe, to come play for the Pontiacs.

Jethroe, who as a member of the Boston Braves became the oldest man to ever win baseball’s Most Valuable Player Award in 1950 at the age of 33, returned to Erie after his playing days, operating “Jethroe’s Steakhouse” for decades. In the 1990s he sued MLB over lost pension, accusing the league of having delayed his playing career by years due to its policy of racial discrimination. Although the case was dismissed, Major League Baseball began offering pension benefits to Jethroe and other former Negro League veterans who made it to the major leagues late in their careers.

Depression-era calls for greater social reform were heightened by the outbreak of World War II. Throughout the war, millions of African Americans labored in factories and served abroad under the banner of the “Double V”—a phrase coined by the Pittsburgh Courier that denoted Victory over the Axis powers abroad and against racism at home. The sharp contradiction of American ideals and the reality of a racist society was made acutely clear by the experiences of men like Fred Rush, Sr. As a soldier, he endured being moved to a shabby “colored only” rail car, while Nazi POWs rode ahead of him and other black patriots in greater comfort. When he and other African American veterans returned home, they were compelled to establish the Perry Memorial Post #700 because the American Legion would not welcome them.

In the 1950s, as the Civil Rights Movement gathered strength across both the South and the nation, local leadership of the NAACP worked to address racial discrimination in a number of areas, including leveling a suit over a longstanding prohibition against black high school students attending skating parties. The Erie School District superintendent ultimately forced local rink owners to allow integrated parties.

As elsewhere throughout the country, discrimination in employment persisted. Some businesses hired African Americans only for lower paying jobs “in the back” like cleaning or stocking shelves where there was no contact with the public. In 1954, the Governor’s Industrial Race Relations Commission reported that 81 percent of firms in northwest Pennsylvania engaged in racial discrimination.

The NAACP also focused on the deplorable conditions of much of the housing in minority neighborhoods. Rental properties on Franklin Avenue, for example, looked more like rundown sharecropper shacks from the days of slavery. They lacked indoor plumbing, while a communal spigot was the only available potable water.

A group of clergymen organized the Erie Community Relations Commission, one of the first such bodies in the state. Aimed at addressing issues of racial discrimination and fostering interracial understanding, the commission received few complaints in its first years—more than anything else, a reflection of longstanding distrust and resignation that speaking out was pointless. Indeed, as late as 1968, a Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission Report noted that black residents had “developed a profound sense of alienation from the processes and programs of government.”

As the commission expanded its educational work in the late 1950s and the civil rights movement raised the consciousness of the nation, the renamed Human Relations Commission (HRC) fixed its eyes on the housing issue. Their research and advocacy confronted the shocking conditions of city slums and called for efforts to address systemic issues in poor and minority areas.

The HRC also shed light on the fact that many black families could afford to move out of distressed neighborhoods, but were prevented from doing so by an insidious pattern of realtors being unwilling to offer homes to African American buyers outside prescribed areas of the city, a practice known as “redlining.” Those who were able to move into predominantly white neighborhoods were often met with open hostility. In other areas—most painfully, the Peach-Sassafras corridor—African Americans faced abrupt displacement as the result of “urban renewal.”

Many Erie citizens, black and white, participated in national civil rights events. In June 1963—just weeks after fire hoses and German Shepherds were sicced upon children in the streets of Birmingham and Alabama Governor George Wallace made his infamous “schoolhouse door” stand, nearly 1,000 African American and white supporters of the NAACP rallied in Perry Square against the failure of city government to address job discrimination.

During the bloody climactic battle for voting rights in Selma, Alabama in March 1965, local citizens marched, prayed, and raised funds to support local activists in Selma. Less than a week after Boston minister James Reeb was beaten to death on the streets of Selma, on March 14 hundreds of citizens marched two and a half miles in rain and snow, singing hymns along the way. At Shiloh Baptist Church, they heard Rev. Jessie McFarland preach in memoriam for Rev. Reeb, imploring citizens to continue marching, “until no man alive distinguishes between black and white, until every man is free, no man is free.”

A busload of 26 Erie patriots traveled to Selma, Alabama for the final stretch of the 54-mile march to Montgomery, a contingent organized by NAACP leader Jesse Thompson. Mr. Thompson’s cousin Ida Page recalled decades later marching toward Montgomery with people from around the nation, and as far away as France and Germany. Sister Carolyn Herrmann, President of Mercyhurst College, led a campus march of 200 students and faculty in support of Selma marchers. “We are so comfortable, so privileged, so unaware of what it means to suffer insults and indignities,” Sister Carolyn declared. Singing “We Shall Overcome” and “Blowin’ in the Wind,” the crowd marched, “united] in prayer and charity and . . . solidarity with our brothers in chains.”

Erie did not escape the darker side of ‘60s social change. As Detroit and other cities exploded in racial violence in the summer of 1967, on the night of July 12 a riot ensued near the corner of East 18th and Holland. African Americans had been playing craps when police arrived, using police dogs to help break up the gathering. The militant resistance to the actions of police lasted the night. “Erie’s Negroes have been ‘good’ as the saying goes. But not because they have been treated good,” declared Nola Myers in the Erie Morning News the next day. That afternoon, Mayor Louis Tullio met with members of the black community to hear their grievances and find solutions to problems in the 18th and Holland area, including adequate housing for residents and a community center for recreation.

Tensions continued to simmer, and on July 18, the M.P. Radov Corporation at 1925 Holland Street fell went up in flames, a fire apparently set by local young men. Almost three years to the day of the Radov fire, another major fire, suspected to be arson, erupted in the area of the Arthur F. Shultz Co. Building and Sharkey’s Auto Service.

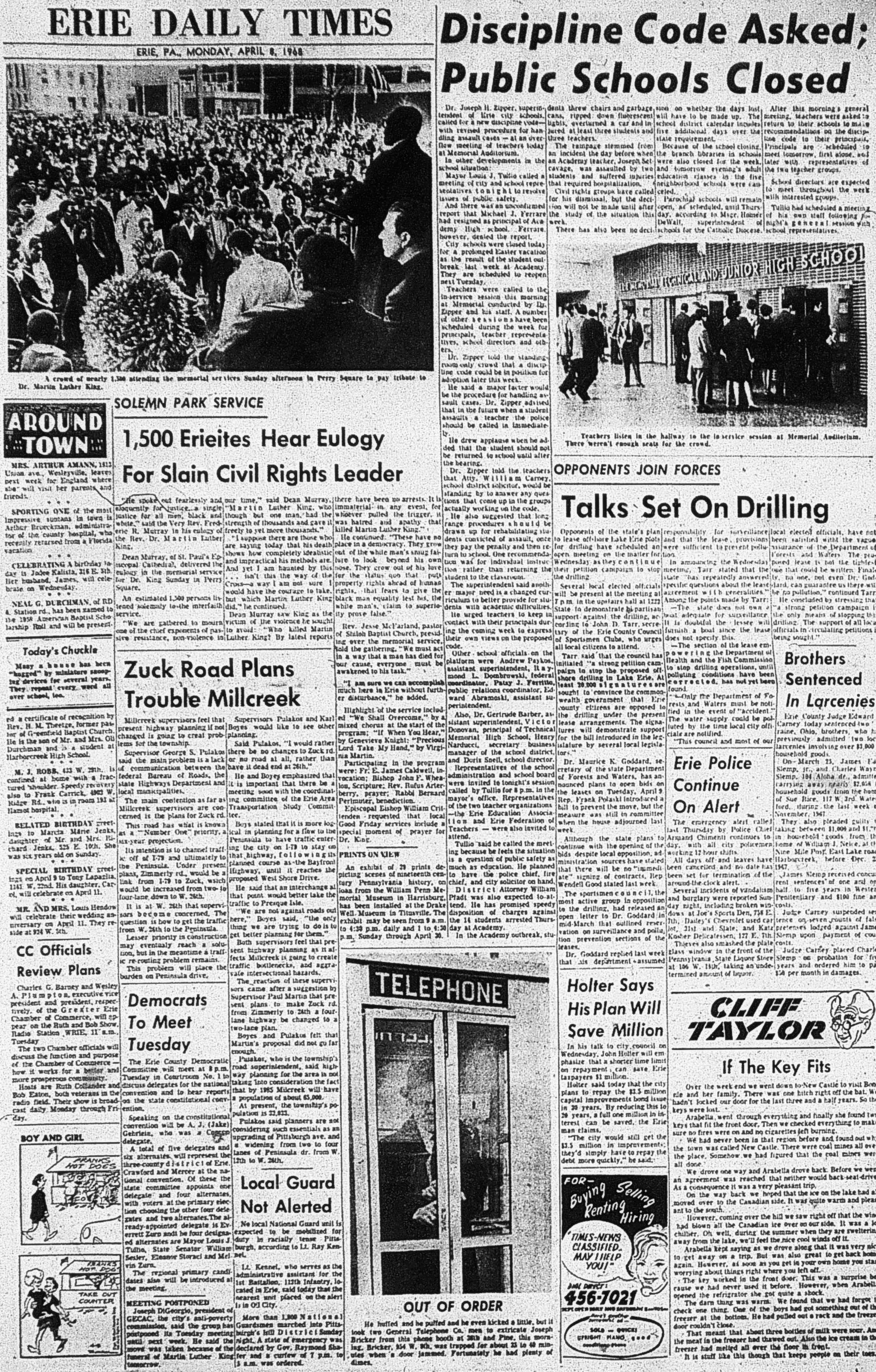

To many civil rights leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the militant protest of the late-60s that sporadically erupted in episodes of property destruction represented the inevitable result of young men trapped in a seemingly hopeless system rigged against them. Though it was hard for most white Americans to understand, many of these incidents were rational, perhaps inevitable reactions to longstanding conditions of mistreatment simply awaiting a triggering event. Such was the case with the uprising at Academy High School on April 4, 1968, set off by an incident the day before. A white teacher had hit an African American student with a wooden pointer for not quickly enough obeying the teacher’s order to return to his seat, provoking the student to a physical altercation. Another black student joined in and the teacher was injured. The principal immediately suspended the two students.

The following day, a number of students petitioned the principal, seeking the return of their suspended classmates and asking hat they be allowed to give their account of what happened. As word spread to the cafeteria that the principal tore up the petition, students launched a disturbance that then spilled out into the streets. Several cars were damaged, one being overturned. Fourteen students were arrested. Smaller uprisings soon erupted at other Erie schools.

Overall, however, Erie managed to avoid in these years the kind of violence and police brutality that took the lives of 90 people in every major American city—almost all of them black. Three days after the assassination of Dr. King in Memphis on April 7, a crowd of 1,500 turned out in Perry Square to peacefully memorialize the slain civil rights leader.

The response to the Academy Revolt proved a disappointment. Instead of dealing with the problems underlying the Academy teacher’s behavior and students’ response to such disrespectful treatment, the Erie School District established “Crisis Classes” for “problem” students. Parents organized the “Concerned Parents” group and criticized these classes as punitive, targeted towards African Americans, and having no instructional value.

For the black community however, the uprising represented not a grim conclusion but the start of a vibrant era of activism. Students and parents lobbied for the hiring of more African Americans in all positions, changes in the curriculum and disciplinary practices, improved conditions, non-racist instructional material, and changes in administrators’ and teachers’ attitudes. In 1970, many black students boycotted classes to raise public awareness of deplorable conditions and racism in the public schools. In April, 1972, students presented the Erie School Board a list of demands, including the end of illegal school suspensions and more equitable opportunities for black athletes.

The ACT(ion) Center at 138 East 18th Street called for a boycott of Academy and for parents to send their children to ACT instead, where they would attend a “Freedom School,” one that echoed the Freedom Schools of the historic 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer. In March 1970, the Freedom School proposal was the focus of a “Black Monday” protest at the Booker T. Washington Center. Drawing a crowd of 1,200, protesters demanded the district step up the pace of change.

Topping the list of grievances was the glaring failure of the Erie School District to hire more African Americans. Despite the growth of the city’s black population in the 1950s and 60s, a grand total of 10 African Americans could be counted among the district’s 1,658 employees. Eight of 874 teachers, and one of 29 counselors were African American. Activists’ demands for the hiring of more African American teachers and support personnel finally met some success, as the Erie School District launched a recruitment drive from Southern Black Colleges and cities with large African American populations. That initiative brought a wave of young black educators and administrators to the Erie area like James Murfree, Nathaniel “Nat” Turner, and Johnny Johnson.

By the time this new generation came aboard, it had been nearly three decades since the hiring in 1946 of Ada Louise Lawrence at McKinley Elementary School—the first full-time African American teacher in Erie public schools. The daughter of Earl Lawrence, Ada had graduated from historically black Cheney State Teachers College and taught in a segregated district in Maryland before her Erie appointment. In the language of the era, an Erie newspaper heralded Ada Lawrence as “a credit to her race,” and expressed the “hope that her teaching career [would] be a long and successful one.” Indeed it was, as Ada Lawrence taught 36 years in the district before her retirement in 1982. She became custodian of her rich family legacy.

In the 1970s, Ada Lawrence mentored young teachers like Johnny Johnson and Celestine Davis. One of a number of graduates of COPE (Career Opportunities Program in Erie), a collaboration of Gannon College and the Erie School District to train minority teacher’s aides as certified teachers, Ms. Davis championed the teaching of African American history in the schools—one of the demands of the students after the Academy rebellion.

The administration of Mayor Lou Tullio responded to the turbulence of the era in a number of ways. Tullio intensified his push for federal funds from Great Society era anti-poverty programs, and then established Neighborhood Action Team Organizations. Although not always succeeding, the NATO I, II, III organizations worked assiduously to build a network of grassroots leadership in the neighborhoods that would pay dividends for many years to come. The John F. Kennedy Center on Buffalo Road that emerged out of NATO III spawned a number of economic development initiatives and worked to nurture black entrepreneurship. Along with the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center in lower Jerusalem, the JFK Center strengthened and extended the reach of social services, recreational opportunities, and educational programs long provided by the Booker T. Washington Center.

12. Ms. Ada Lawrence

13. Ms. Celestine Davis

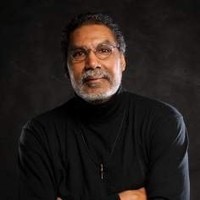

14. Mr. Johnny Johnson

In addition to America’s failure to make good on its promise of freedom and equal opportunity for all citizens, the other issue dividing the nation in the late 1960s was the Vietnam War. One of the most tragically unknown African Americans in Erie history, Larry Hitt, an all-star basketball player at Academy High School, served valiantly in Vietnam. Hitt (later Baqi Ali Diaab) was wounded multiple times when his company was nearly wiped out, ultimately becoming the most decorated soldier of the Vietnam War from Erie County. An expert rifleman and airborne pilot for the 4th Brigade Division, Hitt earned a Purple Heart, Golden Presidential Medal Award, Army Accommodation Medals, Achievement Medals, Good Conduct Medals, and other Army Recommendation Certificates and Weapons Qualifications.

Upon his return home, Hitt’s story took a tragic turn. His wounds led to extended morphine treatment and ultimately, dependency. As with most Vietnam Veterans, Hitt found little support either in the form of drug treatment or in seeking employment. Rejected repeatedly by employers, Hitt turned desperate. He attempted to rob a bank on State Street and then just waited for the police to arrest him. Once imprisoned, Hitt immersed himself in his own spiritual, physical, and educational rehabilitation. Refusing to become embittered, soon he was Baqi Ali Diaab and earning a B.S. in Psychology from the University of Pittsburgh. Released after 25 years in jail, Ali Diaab became a counselor at Harborcreek Home for Boys and remained positive to the end (he died in 2010).

Diaab’s favorite saying was perhaps emblematic for Erie’s African American community as this turbulent, transformational era came to an end: “Keep It Moving.”

Sources

Diaab, Baqi Ali (Larry W. Hitt); at https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/erietimesnews/obituary.aspx?n=baqi-ali-diaab-larry-w-hitt&pid=143125892&fhid=8579, retrieved July 21, 2020.

Nowlin, Bill. “Sam Jethroe,” Society for American Baseball Research; at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/sam-jethroe/, retrieved July 21, 2020.

Page, Ida and Richard, oral history interview (Erie: Mercyhurst University History Department, Public History Program: February 2015).

Strausbaugh, Roy. Foundations of a University: Mercyhurst in the Twentieth Century (Erie: Independent, 2013).

Thompson, Sarah S., with additional research and an essay by Karen James. Journey From Jerusalem, 1795-1995 (Erie County Historical Society, 1996), pp. 49-70.

Image Sources

- Courtesy Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Courtesy Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Courtesy Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Records of the Work Projects Administration, Record Group 69

- Courtesy Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Courtesy Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- https://newpittsburghcourier.com/2018/05/30/memorial-day-historic-double-v-campaign-still-raging/

- NAACP, Public Domain

- UPI Archives: https://www.upi.com/Archives/1965/03/22/300-trudge-peacefully-in-Alabama/9187415642385/

- Tichnor Bros.

- https://www.goerie.com/news/20180408/look-back-april-8-1968

- Courtesy Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Courtesy Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- https://www.jeserie.org/program-lecturers/johnny-johnson

- Getty Images, https://www.thoughtco.com/1965-u-s-sends-troops-to-vietnam-1779379

- https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/erietimesnews/obituary.aspx?n=baqi-ali-diaab-larry-w-hitt&pid=143125892&fhid=8579